Irina, thank you for agreeing to discuss EU-Georgia relations with us.

The Eastern Partnership was launched partly as a response to the Russo-Georgian war in 2008. The EU wanted to increase its presence in the region. Following that conflict, Georgia has lost control over Abkhazia and Southern Ossetia. How would you evaluate the EU’s response to this conflict within the framework of the Eastern Partnership?

On the one hand, it’s hard to put the Russo-Georgian conflict within the Eastern Partnership framework, because this policy’s aim is not to contribute to conflict resolution. It is mostly based on strengthening the EU’s relations with its Eastern neighbours. As to the Russo-Georgian war, the EU played an important role in negotiating a six-point deal and achieving a ceasefire on 17 August 2008. The EU also has a Monitoring Mission (EUMM Georgia) under the Common Security and Defence Policy, located around Abkhazia and Southern Ossetia. There are currently more than 200 civilian monitors working there. The aim is to supervise respect of the ceasefire agreement, however, the EUMM Georgia can’t fulfil its mandate entirely because of the Russian Federation [1].

On the other hand, connecting your question on the Eastern Partnership to the Russo-Georgian war makes sense. There had been hostilities between Georgia and Abkhazia since the 1990s, but back then, the EU was not very interested in the Caucasus. The EU got more involved in the region because of the political impulse coming from Poland and Sweden in 2008. Some EU Member States, particularly after the enlargement that extended EU borders to the East, realised the conflict was affecting the EU’s foreign policy. Another reason why the Eastern Partnership was launched was the creation of the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) the same year. Like the UfM, the Eastern Partnership was conceived as a tool to spread the EU’s normative power and ensure that its neighbouring countries in the East are more stable, more liberalised, and more European.

Georgia signed an Association Agreement including a Deep and Comprehensive Trade Agreement with the EU in 2014, affirming its rapprochement with the EU.

What impact has the Agreement had on your country? How has it affected Georgia’s relations with Russia and the Eurasian Economic Union?

I studied the Association Agreement, and overall, the most important achievement is the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA). The Agreement gave Georgia access to the EU’s internal market. But there are still non-tariff trade barriers such as technical regulations, product standards, geographical indicators, and certification procedures. This means that while the DCFTA accelerates Georgia’s economic development, it doesn’t seem to be a huge deal.

Georgia has a problem concerning economic relations—there had been more connections with Russia in the past. Most people say the DCFTA is generating economic benefits. Maybe it’s a question of time, since EU standards are very high, and it takes a lot of time and resources for Georgia to meet those standards. For now, it’s a little hard to achieve strong economic relations with the EU. But certainly, the DCFTA is already a step towards deeper economic integration. Therefore, at least for me, the DCFTA is mostly a signal that Georgia is getting closer to the EU. Its value is more political.

As to the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), Georgia is not part of it and has never considered joining it. Russia created the EEU as a response to the Eastern Partnership. Armenia, for example, is a member of the EEU and didn’t sign an Association Agreement with the EU.

In my opinion, dependence on Russia is perilous for Georgia, because there have been several economic blockades (a full-scale one in 2005, or an energy blockade in 2006). The good thing was that, as a consequence, the Georgian government decided to be less dependent on Russia and started importing Azerbaijani gas. There also were some embargos on wine—Georgia used to export most of its wine to Russia. However, because of these blockades, Georgia increased its exports to European countries, which is a positive change as these are safer, more reliable markets. This context is another reason Georgia signed the Association Agreement—it guaranteed better market access to Western countries.

Therefore, the signing of the Association Agreement was a consequence rather than a cause of the degradation of Russo-Georgian relations. Georgia’s foreign policy was already pro-West before it. And Tbilisi’s relations with Moscow couldn’t get worse after the 2008 war.

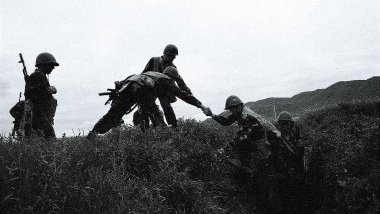

The EUMM Georgia’s tasks are to ensure that there is no return to hostilities and to facilitate the resumption of a safe life for the communities living on both sides of the Administrative Boundary Lines (ABL) with Abkhazia and South Ossetia, © EUMM Georgia

What is the most tangible result of a deepened EU-Georgia cooperation for you?

Personally, I think visa liberalisation has had the biggest impact on me. It was part of the Association Agreement and has been in force since 2017. Because it’s now so easy to visit EU countries, it makes me feel more European. It also helps Georgians, a growingly pro-European population [2] , to better connect to the European Union.

What do Georgians think of an “Eastern Partnership Plus”, proposed in 2017? The “EaP Plus” project is aimed at countries that have achieved significant results in implementing the reforms expected by the EU.

The most important benefits include the prospect of joining the customs, digital and energy union as well as the Schengen zone.

I think that if you ask Georgians about the “EaP Plus”, they wouldn’t know what it is. It might be developed in some other EaP countries, especially in Moldova. You mentioned the customs union promise, but I think an EaP country would have to be significantly developed to get this “carrot.” The Georgian government has done some reforms, but it could do much better in economic terms. It is still difficult for Georgian SMEs to develop, there are weaknesses in the financial system, and the slow and imperfect delivery of justice represents an obstacle for businesses [3]. If the idea behind this proposal is Georgia eventually joining the EU, it has to be really strong economically. If you compare the Georgian economy to the smallest EU economy, Bulgaria, it’s still very far from that.

In August 2019, during a visit to Paris, president Zourabichvili said that Georgia was “ready to take the place of those who want to leave the EU”.

It is true that the pro-European administration in Tbilisi has implemented reforms in order to align with the acquis communautaire, but do you think there really is a possibility of Georgia’s accession to the EU? Do Georgians, especially the youth, want to join the EU?

There definitely is an immense political will to join the EU, and the government is pro-Europe. Nevertheless, as I said, there are a lot of reforms yet to be done. Since the start of the EaP, which was supposed to lead to a big institutional change and good governance, Georgia hasn’t seen such significant changes.

As regards the citizens, most young Georgians would say they’d like to join the EU. It is also the case for the older generation, especially after the war with Russia. But I don’t think it will happen in the near future. The first reason that I’ve already mentioned is that Georgia is not economically ready for that. What is more, if accession talks start, it will represent a threat for Russia, and Moscow would undoubtedly do anything to stop it.

Another factor to keep in mind is that the EU would not envisage just one country’s accession, but rather a region or group of countries. If you look at the other Caucasus countries, they definitely don’t have any political will to be part of the EU. Most Georgians consider themselves Europeans, but I wonder if the other countries in the region feel the same.

What would you say is the biggest limitation of the Eastern Partnership?

Is it the “everything but institutions” approach, specific EaP policies that need improvement, or maybe, the membership of some countries that are reluctant to adopt basic democratic rules?

In my opinion, the biggest obstacle is Georgia not being ready to have a stronger relationship with the EU. Even if the Eastern Partnership is developed further, it won’t be enough. Once the pandemic is over, if Georgia implements additional reforms and proves that there is more than just political will to get closer to the EU, then maybe, the EU might adapt its approach and offer Tbilisi preferential treatment. Perhaps not membership, but accession to the EU customs union for example. Besides this, the Eastern Partnership is the same for all countries, but they have different political aspirations. While Ukraine is ready to do anything to get closer to the EU, countries like Azerbaijan and Belarus don’t care much about it. Obviously, the EaP is also quite unpopular because it does not envisage any enlargement. I think there should be more differentiation among EaP countries—maybe the EU should prioritise countries aspiring for more, like Georgia and Ukraine.

In 10 years, do you think Georgia is still going to be an EaP country, or maybe a candidate country?

In 10 years, Georgia might benefit from a more robust EU policy, something other than the Eastern Partnership. When it comes to accession, does the EU want new Member States? Also, there are other European countries willing to join the EU first—North Macedonia, Albania, Montenegro.

Everything will depend on Georgia’s progress because this is also how the EaP has been developed. Besides the Polish-Swedish initiative, there was some political will in the EaP countries themselves. In the case of Georgia, the last article of the Constitution adopted in 1995 says that “the constitutional bodies shall take all measures within the scope of their competences to ensure the full integration of Georgia into the European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization”. It shows there had been an aspiration to get closer to the EU long before the creation of the Eastern Partnership.

Another important event that emphasises Georgia’s political will and determination to become an EU member state is the President’s visit to Brussels this January. The fact that talks about the application for membership are starting to take place demonstrates that Georgia’s aspiration is not unrealistic, and after going through several significant steps, it might become a candidate country.

Follow the comments: |

|